Introduction

Introduction

Firmware is a critical component of electronic devices. It is the program that is installed on embedded systems that defines their functionality. Firmware is responsible for initializing the hardware components as the computer boots up, enabling the device to function properly.

Attacks against firmware have been of increasing interest to hackers due to their relative ease to exploit in a world of increasingly more secure application- and network-layer security practices. Firmware security has been a frequently overlooked attack surface in cybersecurity that is now relatively unprotected in comparison to other attack vectors such as web applications or operating systems.

In addition, security mitigations such as performing firmware updates are often more costly and inconvenient as they may require updating other software and firmware dependencies on the system, leading to more downtime. In some environments such as hospitals, firmware must pass very strict regulations which can increase the time it takes for updates. Compatibility between the firmware and hardware can result in an additional barrier for firmware updates.

The Rise of Firmware Attacks

Firmware attacks are quickly becoming more common. According to Microsoft, 80% of organizations between the years 2019 and 2021 were victims to at least 1 firmware attack. In many cases, firmware is a single point of failure in the devices of organizations. The privileged nature of firmware allows for it to be abused by cybercriminals to access information such as cryptographic keys in memory, the BIOS/UEFI memory, network traffic, and potentially data from peripheral devices such as SSDs or webcams.

These are some of the techniques used by adversaries once they have obtained firmware-level access:

- Disable security settings such as Secure Boot (BlackLotus)

- Modify the boot record of the system to contain a bootkit

- Wipe the boot record resulting in a bricked system

- Arbitrarily read secrets and other sensitive data from memory

Attack Surface

Attacking firmware can lead to extremely privileged access to a system. For instance, Baseboard Management Controllers (BMCs), Unified Extensible Firmware Interface (UEFI), System Management Mode (SMMs), or management subsystems on the CPU can each be compromised. This section will outline each component’s purpose, security risk, and mitigation techniques.

BMCs

The role of BMCs is to allow remote management of the server. This includes power management, which is the ability to turn the server off and on, and the ability to configure UEFI settings. They often include a built-in keyboard video mouse (KVM) functionality that allows out-of-band access to the display of the server and allows for direct interaction with it through a keyboard and mouse.

BMCs are highly privileged components that may be abused for

- Data theft and exfiltration

- Malware installation

- Disabling security features such as Secure Boot

- Physical damage to the system caused by sending it a signal that increases the voltage to the CPU causing it to overheat

Another attack might include incessant rebooting of the system, rendering it temporarily useless and leading to a loss of availability.

Mitigation

BMC attacks can be mitigated through the following techniques:

- Establishing unique user accounts (if possible) and setting a strong password- ideally one that is in line with NIST’s password guidelines

- Enforcing secure network practices such as not exposing the BMC to the internet and implementing VLAN separation

- Use firmware scanning tools to verify the integrity of the firmware and catch security misconfigurations

- Monitoring BMC integrity through an established root of trust (RoT) such as a TPM or secure enclave in the CPU

UEFI/BIOS

The Unified Extensible Firmware Interface (UEFI) is the modern and prevalent successor to the Basic Input Output System (BIOS).

With access to the UEFI, attackers can

- Wipe the UEFI — the resulting hardware would need to be sent back to the hardware to be flashed with the correct firmware again

- Firmware modification

- Bootkit installation

- Physical damage to the system

An infamous example of malware that attacks the UEFI is BlackLotus, a bootkit that abused CVE-2022–21894 to truncate the SecureBoot policy from memory via the Windows Boot Application, thereby fully bypassing the security measure. Malware with the level of access granted by the UEFI can result in expensive damages to enterprise systems.

SMMs

https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/security/blog/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/SMM-social-2.png

https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/security/blog/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/SMM-social-2.png

The System Management Mode (SMM) is a highly privileged operating mode that is often referred to as Ring -2. The primary benefit of SMM is that it offers a distinct processor environment that is meant for use by only the UEFI/BIOS. The SMM code is executed in its own isolated address space known as SMRAM that is inaccessible to other privilege levels. This isolation is enforced by firmware.

When System Manager Interrupts (SMIs) are issued during runtime, they interrupt the current execution of the CPU and transfer control to the SMI Handler, which is a software routine stored in the firmware that is responsible for handling and processing these interrupts. SMIs are how the UEFI interacts with the SMM.

SMMs can be abused to

- Implant rootkits and bootkits on a system

- Read sensitive data

- Maintain persistence and stealth

Mitigation

Mitigations for SMM attacks can include keeping the firmware updated and using security mechanisms such as Data Execution Prevention (DEP) and Control-Flow Integrity (CFI) on compiled binaries to protect from memory-based attacks.

Management Subsystems

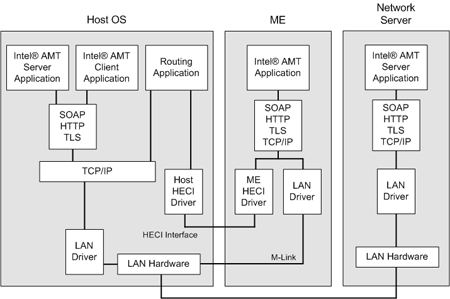

Intel’s Management Engine (ME) or AMD’s Platform Security Processor (PSP) are standalone microcontroller components that allow for out-of-band, remote management of a computer. They are included in the chipsets of these CPUs and, as explained in this article, the ME of an Intel chip in particular has a separated connection from the internal Interconnect, means it has the capabilities to bypass other subsystems like TPM and SMBus.

The ME contains the Intel Active Management Technology (AMT). The AMT provides the remote management and control capabilities for Intel-based computers and servers, even when the system is powered off or the operating system is not running. It is a service that is enabled by the hardware microcontroller that is referred to as the ME.

Despite ME and BMCs having a similar functionality, BMCs are not implemented into the same variety and scale of devices as the management engine is. This can significantly increase the impact of an ME vulnerability.

Well known vulnerabilities in the ME include CVE-2018–3627 and CVE-2020–8703 which can lead to arbitrary code execution and local privilege escalation respectively.

Mitigation

Keeping the software of the CPU updated is crucial for mitigation. The updates can contain patches for known security vulnerabilities on the ME of the chip. In particular, updating the CSME, AMT, I ISM, DAL and DAL Software can prevent vulnerabilities as well as securely configuring the management engine if possible.

Supply Chain Attacks

Attacking the supply chain can involve tampering with the firmware or hardware at any stage in the supply chain including development, manufacturing, distribution, and updating or patching the system. The result can be widely distributed malware affecting countless systems.

In addition to the aforementioned tampering, firmware often uses 3rd-party dependencies (e.g. OpenSSL) which can remain outdated even when included in the latest firmware version. The result is a discrepancy between the firmware and its dependencies which never received an update, despite having critical security vulnerabilities.

One method used to manage supply chain dependencies is using a Software Bill of Materials (SBOM). This is a list of the software components that are implemented into a firmware component. The accuracy and integrity of these lists are crucial to ensure that the known vulnerabilities in the firmware’s dependencies can be identified. There are also commercial solutions that monitor the firmware’s activity and integrity in order to raise alerts when suspicious hallmarks of infected firmware are detected.

Malware Attacks

Another way that firmware can be exploited is through a system that has already been infected. This may happen through social engineering, executing a malicious program, exploiting vulnerabilities in externally facing service, drive-by attacks, and other initial access methods identified by the MITRE ATT&CK framework.

With this attack type, the malicious actor or malware will attempt to elevate their privileges to the highest possible level and use tools such as RWEverything to write to the drivers and firmware. Through this approach, attackers are still able to obtain the privileged access of and stealth granted through firmware-level access.

Firmware Attacks in the Wild

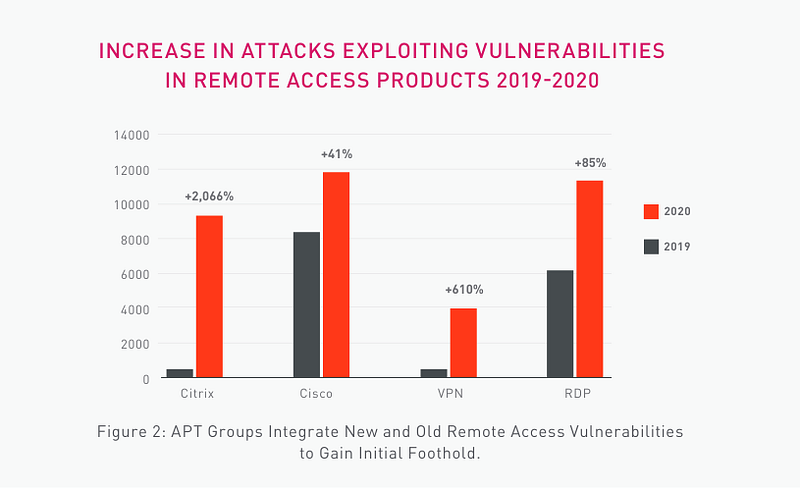

It has become increasingly more prevalent for adversaries to gain their initial foothold on a network through remote access products. In 2020 alone, Checkpoint’s annual cybersecurity report found a substantial increases ranging from 85% to 2,066% of attacks that exploit vulnerabilities in these products as shown in the image below.

Page 25 of Checkpoint’s 2021 cybersecurity report

Page 25 of Checkpoint’s 2021 cybersecurity report

Many of these vulnerabilities are caused by insecure firmware. Examples of this in insecure VPN products are Zyxel’s CVE-2023–33009 and CVE-2023–33010 and Fortinet’s CVE-2023–27997. Both are critical RCEs caused by a buffer overflow that can lead to unauthorized, highly privileged access to a device. This can then be abused to implant malware such as a bootkit or make other critical configuration changes to the system and to move laterally through the internal network.

Mitigations

Security Platforms

Firmware security platforms such as those offered by Binarly and Eclypsium can help to detect and mitigate firmware misconfigurations and vulnerabilities. Binarly relies primarily on AI and deep code inspection to detect known and unknown vulnerabilities and misconfigurations in firmware. Eclypsium’s approach appears to incorporate both crytographic and heuristic verification of firmware with continuous monitoring, although the exact approach of both of these solutions is unknown.

In addition, Lenovo launched their ThinkShield earlier this week, which is also powered by Eclypsium. A testament to the increase in availability of commercial solutions in firmware and supply chain security.

Code Signing

Solutions that use cryptographic signatures to verify the integrity of code can also be used to mitigate supply chain attacks. Unforeseen malware being added to production code, for instance, can be prevented since the changes after the program was signed would be easier to detect.

For instance, Sigstore is an open source project that at a high level uses Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) in order to validate the integrity of different modules in the supply chain to ensure that they were not tampered with. It does this by using a Sigstore client such as Cosign to request a public and private key from the certificate authority Fulcio. The private key that was obtained is used with Cosign to sign the file or image to be verified. After the artifact is signed, the signature of the file, its digest, and public key are stored in Rekor, an append-only transparency ledger that is viewable by the public. The private key is then deleted automatically, removing the need for key management. This system allows for developers, security professionals, and end users to verify that the file they have has not been tampered with.

It is worth noting, however, that while code signing will verify integrity, it does not guarantee that the Software Bill of Materials (SBOM) is fully accurate in its content and completeness in closed-source projects. The security implication is potential lack of transparency on 3rd-party dependencies in these projects leading to unpatched security vulnerabilities in the system.

Initiatives

While firmware attacks are on the rise, there is hope to be found in the initiatives that have been enacted in order to fortify this section of cybersecurity.

Increased Firmware Publications

There has been a rising awareness of firmware security that can be attributed largely to the increased amount of publications in circulation. These may include security best practices, vulnerability disclosures, or news articles.

In June of this year, the Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) and the National Security Agency (NSA) collaborated to create a guide for hardening baseboard management controllers. This document outlined best practices for securing BMCs including many of the techniques that were mentioned previously in this article.

SSITH

In 2017, Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) created their System Security Integration Through Hardware and Firmware (SSITH) program which takes a proactive approach to low-level security.

SSITH is focusing specifically on common classes of hardware weaknesses as identified by the MITRE Common Weakness Enumeration Specification (CWE) and NIST, including buffer errors; information leakage; resource management; numeric errors; injection; permissions, privileges, and access control; and hardware/system-on-chip implementation errors. Researchers are exploring a number of different approaches that go well beyond patching. These include using metadata tagging to detect unauthorized system access; utilizing context sensing pipelines to determine the intent of instructions; and employing formal methods to reason about integrated circuit systems and guarantee the accuracy of security characteristics.

Although it does have a predominant focus on hardware, SSITH still recognizes the role of firmware as an essential component in addressing security challenges and preventing exploit.

SSITH appears to be an ongoing program whose effects have not yet been released publicly.

Secure Development Practices

https://blog.gitguardian.com/content/images/2022/05/21W10-blog-content-stateOfReport-image2.jpg

https://blog.gitguardian.com/content/images/2022/05/21W10-blog-content-stateOfReport-image2.jpg

Cybersecurity has gradually become a significant part of the development process of both software and firmware. More companies are making the shift to a Secure Software Development Lifecycle (SSDLC). With this model, security is a consideration from the conception of a program to its release.

Conclusion

With firmware attacks on the rise and an increased reliance on digital devices, securing systems is an important step of preventing critical cyberattacks. Modern commercial solutions can help to monitor firmware configurations, activity, and supply chain vulnerabilities and the trend towards secure development and education can help to decrease the amount of vulnerabilities that are in the firmware to begin with. In spite of this, firmware will likely never reach a point of having zero vulnerabilities. Maintaining regular updates and continuous education on the latest research is imperative in safeguarding our digital ecosystems, fortifying devices against emerging threats, and fostering a resilient foundation for a secure and trustworthy technological future.